|

| |

|

The flag of Indian Empire from 1879 to

1946. This flag fluttered atop Fort William in Calcutta and many other public

buildings but was seen as a symbol of oppression by nationalists who were to

eventually lead India to freedom from European rule. |

On November 1, 1858, Queen Victoria's proclamation was read

at the Grand Durbar held in Allahabad. The Queen assumed the Government of India

with Calcutta as the Royal Capital. The capital indeed was befitting royalty at

that time. As a contemporary noted, Calcutta's buildings were "all white,

their roofs invariably flat, surrounded by light colonnades, and their fronts

relieved by lofty columns supporting deep verandahs. Calcutta's growth was on,

too. In spite of the turmoil due to the War of Independence, the University of

Calcutta was established in 1857. The new municipal corporation completed the

public sewerage system in 1859, and the filtered water distribution network in

1860. The prosperity of Calcutta invited more immigrants, mainly Armenians from

Iran, Jews from Afghanistan and Iraq, Chinese and Europeans, besides people from

all parts of India. Everybody came because of the excellent law and order

situation or to escape persecution. Calcutta, the last word in colonialism, was

curiously enough, becoming a citadel of freedom simultaneously.

|

Clive Street, 1890 (photograph, courtesy

Bourne & Shepherd). To the north of the old Fort William, Clive Street

became the mercantile hub of the greatest city in Asia at the time.

Headquarters for the stock exchange, banks, shipping lines and merchant and

engineering firms Clive Street was the citadel of laissez faire in the East.

Today, renamed Netaji Subhas Road, Clive Street is the address for the most

business conglomerates in Calcutta. |

Calcutta's reputation as a trading center began to wane at

about this time. The indigo and saltpeter markets collapsed worldwide. China's

anti-opium movement was gaining ground thus choking Calcutta's opium exports. In

1869, the opening of the Suez Canal made Bombay the closest port to Europe and

robbing Calcutta of some of its share of the Indo-European trade. The business

houses on Clive Street were however, not slow to react. Overnight, companies

like Martin Burn, Andrew Yule, Williamson Magor and others moved into a new area

of business. Tea had been cultivated in Assam and Darjeeling for a few years

now, and had been found to be superior to the varieties from China. Overnight,

caskets of tea began to be auctioned on Brabourne Road and began making their

way to the teapots of tea lovers around the world. Not much has changed since

then. The auctions on Brabourne Road continue to this day at the Tea Board

Office, and is indeed a sight every morning. The same companies also diversified

into the other development industries, like metal casting and construction, a

reputation that has survived to this day. This was the time when Calcutta

changed from a trading port to a manufacturing base.

|

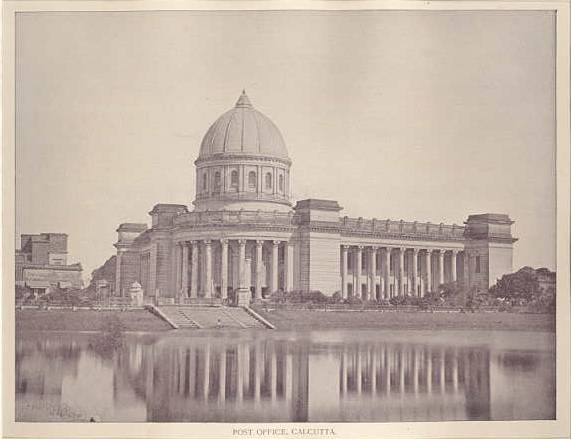

The Imperial General Post Office, 1890

(picture postcard). Built on the site of the old Fort William, the General

Post Office, as it is known today is an imposing edifice on the face of

Calcutta. |

|

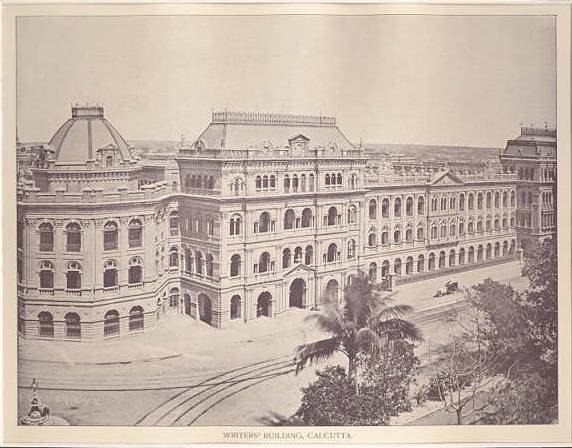

Writers' Building, 1890 (picture

postcard). Then the Secretariat of the Imperial Government of India and today

the secretariat of the Government of West Bengal. Notice the tram lines in

front of the building. |

The 1870s was an important decade for Calcutta. The growth

of public services was remarkable. Horse-drawn tramcars arrived on the streets

of Calcutta in 1873, and a spanking new shopping mall, Stuart Hogg Market, threw

open its doors in 1874. Stuart Hogg Market was well stocked with stuff rarely

found in Asian markets. The first two hotels in Asia had come up in Calcutta

several decades ago. They were the Spence's Hotel, opened in 1830 and now

closed, and the Great Eastern Hotel, opened in 1841, now derelict and awaiting

restoration. Both hotels now grew up into one of the finest in the world. The

political awakening of the region also began at the same time. In 1876, Sir

Surendranath Banerjea founded the Indian Association, the first political

movement in Asia. The Indian Association House stands to this day at the

junction of Bowbazar Street and Central Avenue. In 1877, another Grand Durbar

was held, this time in Delhi, the old capital of the erstwhile Mogul Empire.

Queen Victoria assumed the title of Empress of India and Calcutta became the

Imperial Capital.

|

A label attributable to Jardine Skinner

& Co. of Calcutta from 1890, one of the trading houses that prospered

from the three way trade between London, Calcutta and Shanghai. Jardine

Skinner today has disappeared from all three cities but continues to business

in Hong Kong. |

Calcutta's growth as a major railway junction continued.

The East India Railway ran from Howrah all the way to the outskirts of Delhi in

the North. The Bengal Nagpur Railway ran from Howrah to Nagpur in Central India,

from where the Great Indian Peninsula Railway continued to Bombay. The East

Bengal Railway's line ran from Sealdah, then in the outskirts of Calcutta to the

tea gardens of Assam and Northern Bengal. The Grand Trunk Road was built to

replace the road built by Sultan Sher Shah Suri of Delhi in the sixteenth

century, and now ran from Howrah to Peshawar in the Hindukush mountains. As it

had been true for Rome in an earlier age, all roads now led to Calcutta. In

1886, a pontoon bridge was built to link Calcutta and Howrah without disrupting

the river traffic. Gaslights had been in Calcutta for a while only to be

replaced with electric lighting in 1899. In the 1890s, the largest

telecommunications project ever undertaken in the world bridged the two most

important cities of the world's greatest power. Siemens laid the first cable

between Calcutta and London. Calcutta had arrived as the second City of the

British Empire. In 1919, the construction of the Victoria Memorial was completed

and soon became the jewel in Calcutta's crown.

|

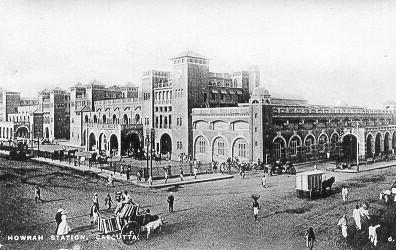

Howrah Station, 1905. Arguably one of the

world's busiest railway stations, it handled then as now, all the traffic

that went west from Calcutta. Situated across the river from the City of

Calcutta, its link to the city has been via a bridge. |

|

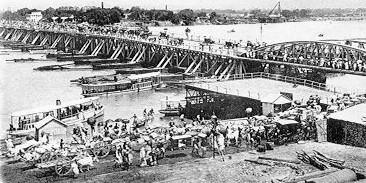

The old Howrah Bridge, from a photograph

of 1905. This bridge was built in 1886 to replace the ferry service to the

main railway station of Calcutta. This bridge had a retractable portion so as

not to encumber maritime traffic. In 1942, this bridge was replaced by the

cantilever Howrah Bridge that we know of today. The old bridge however

continues to be in operation in the Kidderpore Docks. |

Even while Calcutta grew as a city, not all was going well

with its administration. While the citizens of Calcutta had not participated in

the feudal uprising of 1857, their easier access to the world had fueled ideas

of liberty and nationalism. The British ruling class was fully aware of such

aspirations, and Lord Curzon, then Viceroy, promoted the idea of a participation

of the Bengal Presidency, creating two provinces, each of which would have the

local Bengalis as a minority. Such a partition received Royal Assent from King

Edward the Seventh on October 16, 1905. Instead of eliminating political

dissent, the partition inflamed nationalistic feelings and triggered a wave of

terrorism with British officials as targets. The terror culminated in an attack

on Writers' Building itself.

|

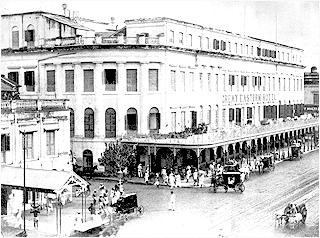

Great Eastern Hotel, from a 1915

photograph. Once regarded as the finest hostelry "east of the

Suez", Great Eastern once boasted of the only clone of the famous

Parisian restaurant Maxim's. The hotel has since gone into an abysmal decline

but there is talk of handing it over to a French company and restoring it to

its past glory. |

In 1911, King George the Fifth at his Coronation Durbar in

Delhi announced that the partition of Bengal had been rescinded. However, the

same announcement also included the transfer of the Imperial Capital to a city

to be built near Delhi. The reason cited was that Delhi was the traditional seat

of all emperors that had ruled India, and should be the same for the House of

Windsor, too, but the actual reason was that the British no longer considered it

safe to maintain political power in Calcutta. The Independence Movement

nevertheless, gained ground in Bengal and soon spread all over India. Calcutta's

leaders, however, belonged to two classes. One that advocated home rule on the

lines of Australia and Canada and the other that believed in terrorism to drive

the British from India. Both groups refused to be drawn along communal lines. By

the 1930s, other leaders from northern and central India, who stressed on

communal values and non-cooperation, had marginalized both groups.

|

The Indian headquarters of the Chartered

Bank of India, China & Australia Limited in 1940. Today this building

serves as one of the principal offices of the Standard Chartered Bank p.l.c.

in India. |

The Independence Movement not withstanding, Calcutta's

economic growth continued. The outbreak of the First World War had little impact

on Calcutta, in spite of the German cruiser Emden rampaging the Bay of Bengal

and blocking tea exports. Calcutta, about 50 miles upstream was beyond the reach

of Emden's guns and Calcutta was spared the shelling that Madras and Penang had

to undergo. At about this time, Indian entrepreneurs broke into the monopoly of

the British and hundreds of jute and cotton mills appeared on both sides of the

Ganges. This was also the time when a large community from the Marwar region in

Western India arrived and began to take over the businesses of traditional

Bengali business families. The best known such family, the Birlas, established a

jute mill in 1918, and began manufacturing Morris motor cars in 1942 at their

Hindusthan Motor Works.

|

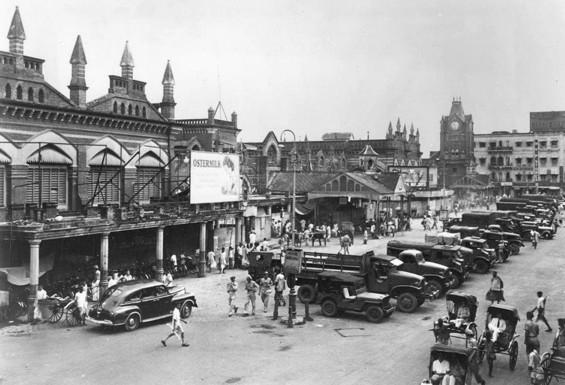

Chowringhee Road, 1940. One of the finest

promenades in the world at the time. As part of the Allied Offensive in China

in 1942-43, three make shift airstrips were built in Burma. They were

nicknamed Broadway, Piccadilly and Chowringhee, which demonstrates the league

that this promenade kept at the time. |

The Golden Thirties was indeed the golden age of Calcutta.

The city knew no shortages. The streets glowed in its electric lights. Trams and

motor buses plied the streets and motor cars were beginning to outnumber

horse-drawn coaches. Theater, cinema and fine dining defined Calcutta's social

life. Great Eastern, Spence's and the newer Grand and Continental were the

finest hotels in the continent. The shops of New Market and stores like the Army

& Navy and Whiteway, Laidlaw & Co. did brisk business, and Peletti's,

Firpo and Maxim's served the finest in French and Italian foods on their tables.

Trains linked Calcutta to all over the Indian Empire and ships of all nations

called at its docks. Even the nascent air travel industry could not ignore

Calcutta. Imperial Airways' service linked Calcutta to London, while Calcutta

was an important stop on the Paris to Saigon and Amsterdam to Batavia services.

The euphoria over Asia's first Nobel Laureate had just been replaced by one for

a Calcutta University professor becoming the second, even as another scientist

was helping the greatest scientist of the twentieth century, Albert Einstein,

unfurl the secrets of science, sitting in its laboratory. Calcutta's hospitals

and medical colleges were producing vaccines for deadly tropical diseases.

Indeed the din of success rendered the occasional explosion of terrorist bombs

and the sounds of demonstration, out of hearing. Chinese chefs and craftsmen

arrived in Calcutta at about this time to escape Japanese invasion or communist

persecution. Calcutta welcomed everybody, to her own advantage.

|

New Market, 1945. Officially built as the

Sir Stuart Hogg Market in the 1880s but referred to this day as the New

Market, this was one of the first shopping malls in the world. Legend goes

that one could buy tiger's milk here at one time, New Market remains a major

shopping center for residents and visitors alike. |

|

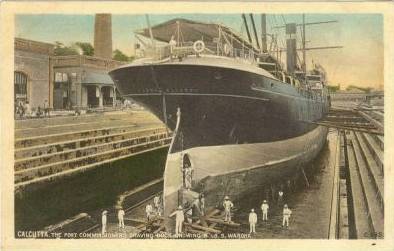

A picture postcard depicting British

Indian Steam Navigation Company's S.S. Wardha berthed at the Kidderpore

Docks. Until the beginning of the second world war, passenger and cargo ships

of all prominent lines around the world connected Calcutta with ports ranging

from New York, Buenos Aires, Liverpool, Venice, Sydney and Honolulu with

regular passenger as well as freighter services. Much disruption happened

during the war, and later the riverine port was found inadequate for larger

ships and slowly went into decline, rather like the Tilbury Docks in London. |

|

Dum Dum Aerodrome, 1944. Calcutta was an

obvious destination for all airlines of the world. Calcutta appeared on KLM's

Amsterdam-Batavia (now Jakarta) route in 1928, on Air Orient's (later renamed

Air France) Paris-Saigon route in 1933 and Imperial Airways' London-Hong

Kong/Singapore route in 1934. China National Aviation Company flew a Shanghai

- Hong Kong - Chungking - Calcutta service in 1937. As a matter of fact, CNAC

shifted its operational headquarters to Calcutta after Shanghai fell to the

Japanese. |

|

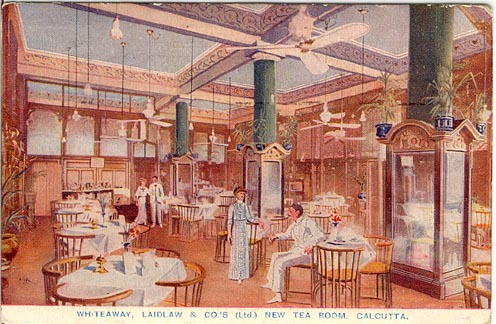

A picture postcard depicting the tea room

of Whiteway, Laidlaw & Co., the famous Calcutta departmental store that

once rivaled Harrod's, Macy's and Mitsukoshi. |

The 1940s brought gloom to Calcutta as with the rest of the

world. As trade collapsed and all energies were channeled into the war effort,

Calcutta watched as the Japanese army overran nation after helpless nation until

it stood at the Eastern borders of India. For the first time since Clive and

Watson restored the Union Jack on Fort William, Calcutta was under direct threat

of invasion. The invasion came this time from the air. Calcutta's dockyards and

several residential areas were bombed, though the damage was very little. Fear,

however, set in and several citizens began to depart the city, even while

refugees from Burma and other areas actually overrun by the Japanese began

arriving by the millions on the streets of Calcutta. And as if its woes were no

less, the parallel agitation for a Moslem homeland in India began to gain

ground. Fueled by the British policy of divide and rule, India burned both under

the impact of the Independence Movement and communal riots. Nowhere, were they

more severe than in Calcutta, in spite of its great tradition in secularism.

Calcutta's contribution to the war effort is tremendous though very often

forgotten. In 1943, Bengal chose to take upon itself the greatest man-made

famine ever, in order to feed the besieged Allied forces in China. For months

the starving masses of humankind watched as supplies were flown over the

Himalayas. The famine resulting from the biggest airlift in history until then

left millions dead.

The Second World War ended with little doubts that the

British would leave. The biggest issue left however was that of the imminent

partition of India into Hindu and Moslem states. As the issue of partition was

being debated in London and New Delhi, the Great Calcutta Killings of August

1946 commenced. The fight between the Indian National Congress and the Muslim

League claimed thousands of lives. The Indian Empire was partitioned on August

14, 1947 creating the two states of India and Pakistan.

|

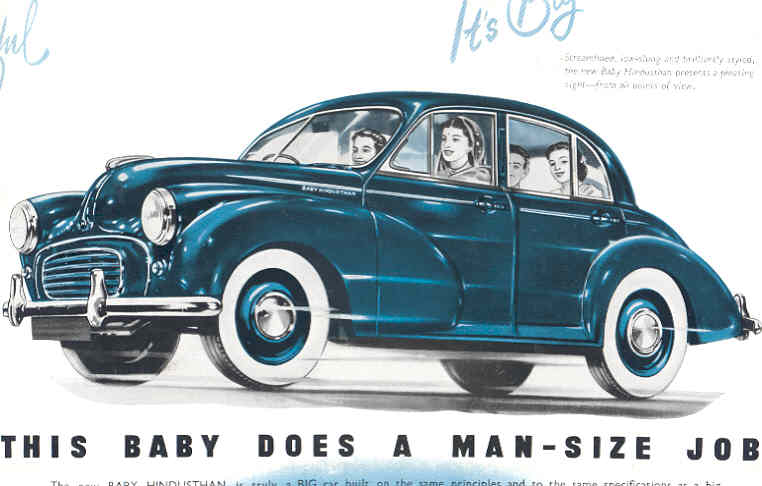

An advertisement of the 1953 Baby

Hindusthan. Hindusthan Motors started manufacturing Morris automobiles at

their factory near Calcutta in 1943. This factory, to this day, continues to

manufacture the Ambassador, the classic Morris Oxford with a minor

variations, the standard taxi cab in Calcutta. |

Calcutta's glory as the second city of the British Empire

ended with the lowering of the Union Jack from the mast atop Fort William on

August 15, 1947. The departure of her creators deprived Calcutta of her special

status, and partisan treatment by the succeeding rulers and the apathy of her

own people led to her rapid decline. However, true to her spirit, she continues

to live and prosper even amongst her seeming dereliction.

|